How To Make World XC Matter

Track & field doesn't need more meets, it needs more meets that matter. Here's a simple solution to make World XC important -- even for those without a shot at a medal

By Jonathan GaultThe morning before the 2024 World Athletics Cross Country Championships in Serbia, Elizabeth Egan ran a workout along the bike path that runs along the Danube River in Belgrade’s Park of Friendship. She noticed something interesting. While half of the course — including the start/finish area, relay exchange zone, and video board — had been blocked off by tall chain-link security fences, the other half was protected by low metal fences that allowed a view of the action.

This, Egan thought, was a good thing. It would give organizers the opportunity to capitalize on the race-day foot traffic moving through the park on an unseasonably warm Saturday afternoon in late March — even if those passersby did not get to see all of the action.

That afternoon, Egan returned to check out the course in more detail. She strolled around the perimeter of the venue, taking notice of the breaks in the tall security fence. Team Entrance. Staff Entrance. VIP Entrance. And…that was it. No spectator entrance. Anyone without a credential, Egan realized, would have to watch from the area she had noticed during her workout that morning.

“It was then like, oh, this is all we’re getting,” Egan said. “Can’t see the big screen, can’t see the finish, can’t see the start.”

Many of the spectators in Belgrade were there to cheer on a friend or family member, but Egan, who had traveled from Ireland for the race, is simply a huge fan of World XC — “I kind of like a niche event,” she said. The problem, Egan said, is that nobody involved with organizing the meet — not World Athletics, not the local organizing committee — seemed to have thought about the spectators at all. Before the race, Egan visited the meet website in search of basic information, such as whether she needed a ticket for the event. She could not find the answer.

“I don’t want a red carpet rolled out for me, but some sort of recognition that spectators are welcome would be nice,” Egan said. “There wasn’t even any signage [on the course] to say ‘spectators this way’ or anything. You’d have more than that at a local open meet.”

Milica Živić, a Serbian former 400m runner who lives in Belgrade and attended the meet, said the event was promoted far less than the 2022 World Indoors and 2017 European Indoors, also held in Belgrade.

“I don’t think the promotion was done well,” Živić said.

The fans who did show up on race day were able to access around half of the course, including up-close views of the major obstacles such as the hay bales and mud pit (though most of the foot traffic along the bike path did not end up staying for the meet). But many of the basic spectator amenities were missing. There were no merchandise tents, and no public bathrooms on the course. Instead, spectators had to wander off and use the facilities at a nearby hotel.

There were also no concession stands — a problem when temperatures climbed above 80 degrees on a course with no shade. Fortunately, there were water stations for the athletes throughout the course, and volunteers were able to give some of those bottles to spectators in need. Others came up with a more creative solution.

“I got a drink from the tanker that was being used to fill up the mud bath,” said another spectator, Emily Evans. “There were some little taps on the back.”

While crowds in Belgrade were not large — there cannot have been more than 500 fans on the course on Saturday — one of the beauties of cross country is that a small crowd can feel bigger because fans are often able to run around the course and watch the race from multiple spots. But in Belgrade, it was not possible for spectators to cross the course. Some of the spots that are traditionally the loudest, such as the home straight and finish line, were largely barren, restricted to those with credentials. A far cry from the raucous grandstand that roared Uganda’s Jacob Kiplimo home to gold in the U20 race seven years ago in Kampala.

“Obviously we would have hoped to have fans down the finishing straight,” said Kevin Sanchez, the top American finisher in the U20 race, whose parents and brother flew to Serbia to watch him compete.

Five years ago, Christine Murphy and Bruce Davies traveled from Sarnia, Ontario, to World XC in Aarhus to watch their son Andrew Davies run in the U20 race for Canada. In that race, they were able to meet Andrew in the finish area. After he cooled down, they watched the senior races together as a family. In Belgrade, where Andrew was competing in the senior race, they were only able to meet him briefly when he snuck out of the accredited area just before the Canadian team was set to depart.

“The biggest thing I missed was the end,” Murphy said. “In Aarhus, we went over and we chatted with the Canadian junior boys when they finished, got some pictures, talked to the coach. That milling about at the end with parents and families, which is such a big part of it, was gone.”

LetsRun.com asked World Athletics why spectators were barred from the finish area in Belgrade. World Athletics referred questions to the local organizing committee, which did not respond to LetsRun.com.

In Belgrade’s defense, the city only had six months to plan the championships after taking over when World Athletics pulled the meet from the Croatian cities of Medulin and Pula. By all accounts, the athletes were treated well and the course, while basic, still featured elements that challenged runners.

And despite the spectator pitfalls, Egan, Evans, Murphy, and Davies all said they enjoyed their experience at 2024 World XC. But Davies, who had also been to Bathurst last year to watch his son compete, said that while Belgrade had been a fun afternoon at the races, it could have been so much more — a common sentiment among those interviewed for this story.

“This was a smaller crowd than our regional high school meet,” Murphy said. “It didn’t have that championship vibe and energy that were present in Aarhus and I think in Bathurst.”

“The good thing about cross country normally is that you get very close to the action and you can run around and go to various spots on the course and see the whole race,” Evans said. “That’s what we missed here in Belgrade, and that’s one of the things that makes cross country so good. You need to have spectators involved to make athletics enjoyable, and we lost it on that occasion. Having only the media and VIPs have access to view the start and finish is a step backwards.”

***

Looking ahead to Tallahassee 2026

The good news, as the countdown begins to the next World Cross Country Championships, which will be hosted in Tallahassee, Florida, in 2026, is that the spectator problems of Belgrade should be a relatively easy fix. In fact, Tallahassee already has a course mapped out with fan experience zones.

Promotion should be better as well. Tallahassee has known it will be hosting since July 2022, and considering the number of fans who traveled to Orlando in February for this year’s US Olympic Marathon Trials, it should not be a hard sell to convince a few thousand fans to take a midwinter trip to sunny Florida for the first World XC on US soil since 1992.

No, the issues with World Cross Country are more structural. The fundamental one is this: too many of the top athletes and federations view World XC as optional. There are various reasons for this, from the timing of the meet to East Africa’s domination to the primacy of the Olympics and its qualification system. But the result is that many of the top distance runners routinely skip World XC in a way they never would on the track.

This is not a new issue, nor does it mean that World XC as currently constructed is completely broken. The headline of this piece, “How to Make the World Cross Country Championships Matter,” is slightly misleading in that it suggests recent editions did not matter at all. That is not the case.

World XC crowns a world champion, and a lot of great runners show up to fight for that honor. Bathurst 2023 was stacked with top-end talent — the men’s race featured the world 10,000 champ Joshua Cheptegei against the World Half champ Jacob Kiplimo against the Olympic 10,000 champ Selemon Barega while the women’s race featured world 10,000/half marathon record holder Letesenbet Gidey and rising star Beatrice Chebet. But not every edition is as talent-rich, and for too many countries — the US included — World XC does not matter nearly as much as it should.

As a spectacle, World XC is a great event. The atmosphere in Kampala in 2017 was electric. The course in Aarhus in 2019 was one of the toughest — and best — ever devised for a cross country race and resulted in a fantastic day of racing. Bathurst 2023 was a success. But this year’s event in Serbia was a step back. And World XC cannot afford any more of those if the event is to thrive long-term.

World Athletics president Seb Coe is a cross country fan and has long stressed that there is a place for the event in modern distance training. He would like to see World XC continue, and it should, as long as cities remain interested in bidding for it.

“It’s still an important property and has a historic place in our athletics landscape,” Coe said in Belgrade.

But Coe also admitted that when it comes to World XC, “We’ve got work to do.”

“I would like to see more of our European nations supporting and travelling to these championships,” Coe said.

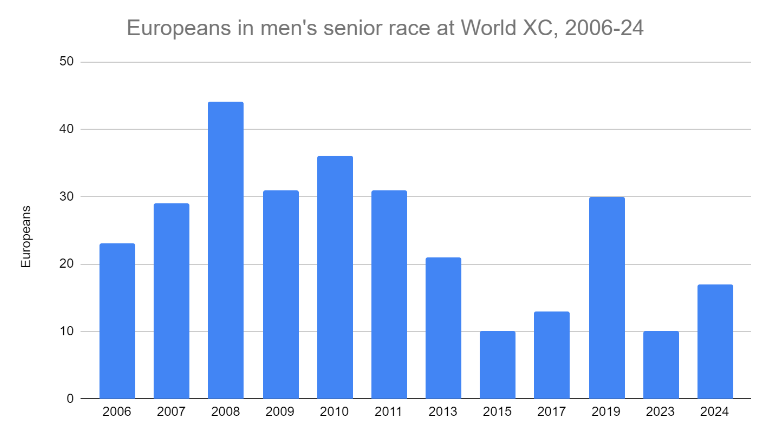

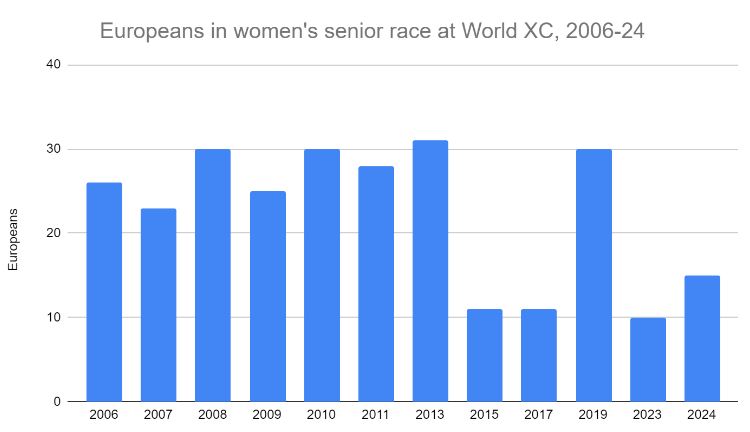

European participation is down in recent editions. The last five World XCs have featured an average of 16.0 European men and 15.4 European women in the senior races, compared to 32.6 and 28.8 in the five editions from 2008-13. Those numbers are somewhat skewed given four of the five World XCs from 2008-13 were held in Europe compared to just two of five from 2015-24. But it is worrying that the numbers from the 2024 championships on European soil — 17 European men and 15 European women — were substantially lower than the participation numbers from 2006 (23 men, 26 women) and 2007 (29 men, 23 women), events that were held in Japan and Kenya, respectively.

Europeans still like cross country. Ninety men and 58 women ran in the senior races at the most recent European Cross Country Championships in Brussels in December. But most European federations — Great Britain and Spain excepted — have decided it is not worth sending teams to a meet where their athletes have little chance of finishing on the podium.

Europeans still like cross country. Ninety men and 58 women ran in the senior races at the most recent European Cross Country Championships in Brussels in December. But most European federations — Great Britain and Spain excepted — have decided it is not worth sending teams to a meet where their athletes have little chance of finishing on the podium.

Since 2005, only one European team — the Portuguese women in 2006 — has earned a medal in the senior race at World XC with the Kenyan-born Lornah Kiplagat of the Netherlands the only European individual to medal in that span. Over the last five editions, 92% of the top-10 finishers in the men’s and women’s senior races have come from just three nations: Kenya, Ethiopia, and Uganda.

But East African domination at World XC is nothing new. East African runners are also really good at running 10,000 meters on the track; it stands to reason they would be good on a 10,000-meter cross country course. So why is East Africa so much more dominant in cross country than on the track?

It’s pretty simple. The non-African runners winning medals on the track rarely run at World XC. Here are the last 10 non-African athletes to medal at Worlds or the Olympics in the 5,000 or 10,000 meters, along with how many times they ran World XC as pros:

| Athlete | Country |

World XC appearances (senior race)

|

| Galen Rupp | USA | Never |

| Emily Infeld | USA | 2013 |

| Mo Farah | Great Britain | 2003, 2005-07, 2010 (0 after his first track medal) |

| Konstanze Klosterhalfen | Germany | Never |

| Paul Chelimo | USA | Never |

| Moh Ahmed | Canada | 2013 |

| Kalkidan Gezahegne | Bahrain | Never |

| Mo Katir | Spain | Never |

| Sifan Hassan | Netherlands | Never |

| Jakob Ingebrigtsen | Norway | Never |

So of those 10 athletes — a list that includes some of the biggest names in the sport over the last decade — just three ever ran the senior race at World XC. And two of those come with caveats since Farah never ran it once his career took off on the track in 2011, while Ahmed’s only appearance came in 2013 while he was still in college at Wisconsin.

The top African runners have a much higher participation rate. Selemon Barega ran the next World XC after winning the Olympic 10,000 in 2021. Joshua Cheptegei has won the last three World 10,000 titles and has run the last four World XCs. Letesenbet Gidey ran World XC in 2023 after winning Worlds on the track the previous year. Hellen Obiri ran World XC in 2019 after winning Worlds on the track in 2017.

So what fixes are in order? We can think of two big ones that would improve World XC immediately, plus one more that World Athletics is already on its way to fixing.

1) Make World XC the way to qualify for the 10,000 at Worlds and the Olympics

Let’s call this “the Robert Johnson rule” since my boss and editor is the one who came up with it on last week’s LetsRun.com Track Talk Podcast.

The past two years have shown that as long as the Olympics and track World Championships remain the most important events in the sport, athletes are going to blow off World XC in order to prioritize those meets. You think Grant Fisher, Joe Klecker, and Alicia Monson don’t like cross country? Of course they do. But the Olympics and Worlds are more important to them. Instead of World XC, they’d rather chase an auto standard or avoid breaking up training by traveling halfway around the world for a race. And you can’t totally blame them: the incentive structure of the sport prioritizes the track.

So how do you get them to show up to World XC? Change the incentives.

There are 27 spots on the startline for the World and Olympic 10,000-meter finals. Make it so that almost all of those spots are earned through the World Cross Country Championships.

Here’s how it would work: the top 24 finishers at World XC (after limiting it to three athletes per country) unlock spots in the next global track championship for their country. From there, it is up to each country to determine how to allocate those spots. This fixes three problems at once:

I) The best athletes will run World XC

If you’re a top 10,000-meter runner, are you going to sit out World XC and hope that your country earns its spots? Maybe if you’re Kenyan, Ethiopian, or Ugandan. But most other athletes would be faced with a choice: run World XC or risk missing out on the 10,000 at Worlds or the Olympics.

II) Standard-chasing in the 10,000 would be eliminated

Championship racing is more exciting than time trialing. Instead of having top athletes run a time trial 10,000 to qualify for Worlds or the Olympics, they’d be qualifying via World XC — a global championship where places matter and there is actual prestige for winning. That’s a win for the sport.

III) National championships would matter more

The best thing about a US championship is that it is cut-and-dried — the top three finishers across the line make the team, fourth place goes home devastated. At least, that is how it is supposed to work.

But that is not always how it works in practice. Sometimes, there are only four or five athletes who have the requisite qualifying standard or world ranking to make the team. So if 2nd or 3rd doesn’t have the standard, suddenly we’re paying attention to 4th or 5th. Or we’re trying to figure out if 2nd or 3rd place has enough world ranking points to displace…and your head is spinning. Championships should be simple, not complicated.

We’ve said it before and we’ll say it again: if a country is going to have three athletes in the Olympic final regardless, they should be able to hold a trials and send anyone from the top three — not just the athletes with the standard.

***

But wait, you say. How can you award spots in a track 10,000 to athletes based on cross country results? They’re different events.

Our answer: so what?

Under the current qualifying system, eight of the 27 spots in the Olympic 10,000 field are determined by world cross country ranking — a system that can be gamed by amassing points at uncompetitive meets. Awarding spots based on finish at World XC makes more sense than that.

Plus look at the marathon. Right now, the vast majority of athletes get their Olympic marathon qualifiers in races like Valencia or Seville that feature flat courses, perfect weather, and great pacemaking. The Valencia and Seville Marathons are nothing like the Olympic marathon, yet that is how you qualify for the Olympics. Using cross country results to qualify for a track 10,000 is not much different.

You don’t need to have 100% of the qualifiers come from World XC — it might be good to leave a few spots open in case a megastar is hurt and can’t run World XC. Maybe it’s not the top 24 from World XC but the top 20 or top 22. And since World XC is currently only in even years, you’d have to figure out a way to synthesize that with the Worlds/Olympic schedule — perhaps by holding World XC three out of every four years to mirror the global track championships. But the basic point stands: if you link World XC with Olympic qualification, either the stars will turn up at World XC or they will abandon the track 10,000 entirely.

2) Don’t put World XC and World Indoors in the same year

Starting in 2011, World Athletics switched World XC from an annual event to biennial. The timing made sense. In even-numbered years, distance runners could either drop down and run World Indoors or step up and run the World Half. In odd-numbered years, they ran World XC.

Now the calendar is totally different. The World Half is now the World Road Running Championships and has moved to the fall so that runners can do it just after the track season wraps up. And both World XC and World Indoors are being run in even years with nothing in odd years.

The overlap is not huge between athletes running World Indoors and World XC, but there is an overlap. Moreover, it just doesn’t make sense for World Athletics to have two of its championships in close proximity in even years and nothing at all during the corresponding dates in odd years.

World Athletics has been looking at bringing the date of World XC forward so that athletes gearing up for Euro XC can run both meets more easily — the next World XC will be on January 10, 2026, the earliest in history. If a January date increases participation, great. But it should be January of odd-numbered years.

The exception here is if World Athletics can somehow convince the IOC to put cross country in the Winter Olympics, something we are strongly in favor of but appears unlikely to happen.

3) Make the course challenging and unique

The Belgrade course paled in comparison to the two previous editions in Aarhus and Bathurst. Part of that is because Belgrade had to step in at the last minute and did not have the same amount of time to design a course. But part is due to the venue. The Park of Friendship is the same venue that hosted Euro XC in 2013, and it just is not a great site for cross country. It’s flat and nondescript, barely distinguishable from hundreds of other parks across Europe. Even a skilled course architect would have trouble turning it into an amazing cross country course.

That said, the racing was still pretty good in Belgrade. The hay bales presented a unique challenge, and the fact that athletes chose a mix of hurdling and weaving means they were spaced perfectly — there was no clear best option for going through them. And the mud pit made the race look like “real” cross country, even on an 80-degree day. Both of those innovations should remain for future editions.

But what set Aarhus and Bathurst apart from Belgrade — in addition to the hills — was a sense of place. Aarhus, with its monster climb up the roof of a museum, felt unlike any other course in the world. Ditto Bathurst, whose course ran through a vineyard and was located in the middle of an auto racing track.

The point here is that cross country is not the same as track. Runners should face challenges they don’t face on the track, and the venues should feel unique. This is not a “fix” in the same way as the first two points — recent local organizing committees in Aarhus and Bathurst have already done a great job of this. But it is something to remember moving forward.

Talk about this article on the LRC fan forum / messageboard: What do you think of our proposal to make World XC the primary way to qualify for Worlds/Olympics in the 10,000?